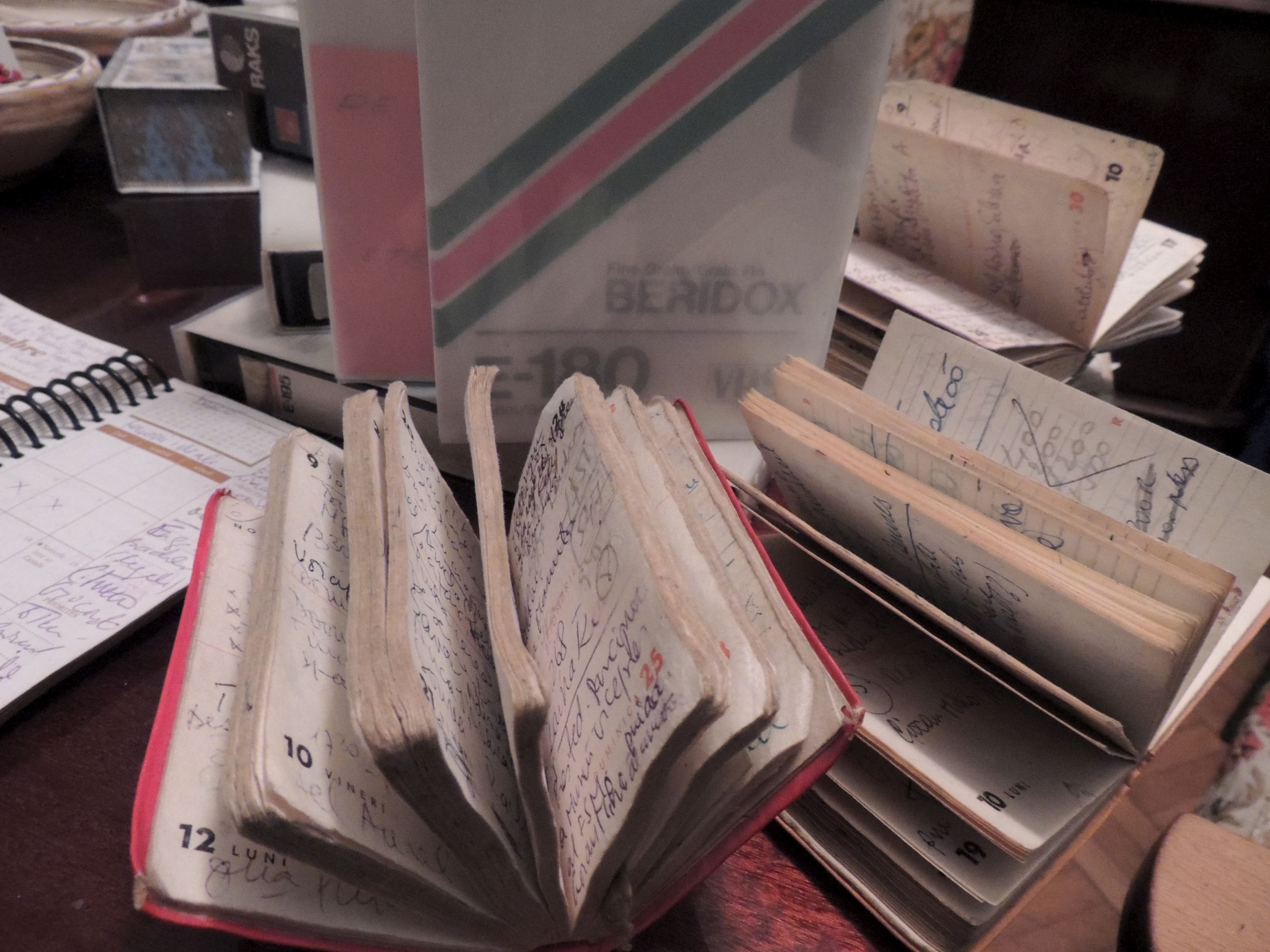

In the Irina Margareta Nistor Private Collection, there are ten notebooks in which are recorded the titles of all the films translated and dubbed before 1989. Basically, these constitute a sui generis inventory of her activity in connection with the translation of video cassettes. The titles of the films recorded in these notebooks respect the criterion of chronology: they are organised by days, months, and years. The entries are made in pen, ballpoint, or pencil. The owner of the notebooks mentions nostalgia as the decisive reason for her having kept them: “The notebooks in which I listed the films help me to recall exactly what I did back then.” The films translated include all possible genres, from Oscar-winners to mediocre productions, from drama to comedy, from romance to police films, from cartoons for children to action films with violent scenes that nowadays would be forbidden to minors. Their common denominator was their Western provenance and their distribution without going through the editing imposed by censorship, which would have resulted in all scenes considered problematic being cut.

Irina Margareta Nistor believes, however, that it is essential that all the translations she made before 1989 be discussed within the binomial “constraint–freedom,” which in this case was no longer defined by the censorship imposed by the communist regime, but by a self-censorship that depended on personal criteria. According to her analysis of her own translation activity, such a discussion “automatically comes round to the terms ‘constraint–freedom.’ On the video cassettes, I translated absolutely everything. Apart from the swear words – and I would like to dwell a little on those. When I was putting my voice on the video cassettes, I didn’t translate exactly how they swore in English. But this wasn’t a matter of censorship. It was a matter of upbringing. In my home, no one ever swore; my parents didn’t swear; my grandparents didn’t swear. And I couldn’t say such things either. We had political prisoners in our family. And I knew about those methods of torture – when they made them swear at their dead, their mothers, brothers, fathers, sisters. With hard swearing. And I said: ‘I don’t want my voice to turn into a torturer’s voice.’ From outside, what I’ve just told you may sound peculiar. It’s not at all. It seems to me perfectly normal to refuse to swear. No one was censoring me – as some might perhaps think. The communists swore horribly. I could have put those swear words on the video cassettes. When they got angry, they could swear like anything. And that includes the women. But I refused to do it.”