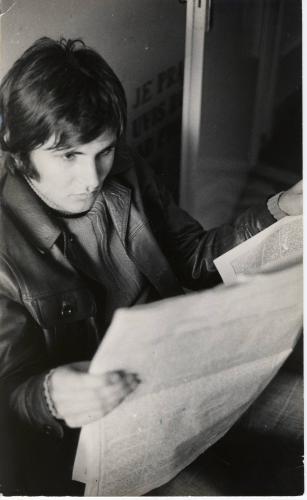

The interview is not dated; however, we can say that it was made in the early 1980s. It has special importance for researching the dissident movement since it explains Đinđić’s activism and engagement in student organizations, his arrest, trial and subsequent release.

Đinđić was one of the members of the Ljubljana Six. This was the name of a group of students arrested in Ljubljana in 1974, and prosecuted under the accusation of “hostile activity.”

At the beginning of 1970, there was a clash of the Communist Party with a group of professors, especially with the so-called Praxis circle, gathered around the Praxis journal. This was only a part of broader restrictions of political, intellectual and artistic freedoms in Yugoslavia. The clash with the group of professors was a topic of discussion throughout academia. It also gave impetus for the Students’ Union of the Faculty of Philosophy to initiate a meeting in Belgrade in December 1973. Zoran Đinđić was at this meeting and spoke about its conclusions: “We see the Faculty of Philosophy as a humanistic institution with a firm communist commitment. None of the members of the Faculty can be disqualified as [an] enemy of the self-governing socialism. Therefore, we are strongly against the exclusion of the so-called ‘group of professors’ from the Faculty’s political principles. In accordance with this, there cannot be a mention of removal of any member of the Faculty of Philosophy.” (Popov, 1989, 130)

Subsequently, in January 1974, students from the three most important Faculties of Philosophy in Yugoslavia (Belgrade, Zagreb and Ljubljana) met in Ljubljana to discuss a joint effort. On this occasion, a Draft Resolution on the Situation in the Country was presented. The draft criticised the repression of and restrictions placed on the autonomy of the university. It is important to mention that the critique came from the leftists and that the draft emphasized the socialist Marxist values of the Union of Yugoslav Communists. The attempt to unify students from different republics and the public reading of the draft provoked the Party’s attack on the student leaders. In the interview for Student, Đinđić said: “It was the time when I worked within the framework of FCSU (Faculty’s Council of Students’ Union). Then, in 1973-1974, it was clear that the Youth Union will replace the Student Union. This reorganization was obviously meant to neutralise FP (Faculty of Philosophy), as a precondition for making personal changes they cared about, and we tried to postpone the collapse of the Student Union. One of the possibilities was to establish a parallel autonomous organization, so that, when the official one would be banned, the parallel organization would declare itself as the official. Thus, for at least some time, there would be two organizations – Youth Union and Student Union. Fifteen of us from FP from Ljubljana, Zagreb and Belgrade met in Ljubljana in order to make a common platform for this kind of organization, but this was forbidden and we were called to trial...”

The authors of the draft were convicted and sentenced to prison, and the Students’ Union was dissolved. The convicted students were Vinko Zalarj and Sarko Štajn from the Faculty of Philosophy in Ljubljana, Lino Veljak and Mario Rubi from Zagreb, and Miodrag Stojanović and Zoran Đinđić from Belgrade. Zoran Đinđić refused to defend himself at the trial and was sentenced to one year imprisonment for criminal acts of “hostile propaganda” and “conspiracy against the state and against the social system.” It is important to note that the Party reacted even though the criticism came from declared leftists/communists. Thus, the Party wanted to keep the right to critique to itself. It was not only important what was being criticised but, also, who was criticising.

Regarding the verdict, Đinđić said, “A year in prison, which was changed to probation due to public pressure. Going to trial was more interesting than the process. A couple of us from Belgrade and Zagreb met with people from Ljubljana, we had a dinner somewhere and discussed what would we say tomorrow at the trial. Someone invited us to stay at his place outside of Ljubljana, on the Sava bank. Around midnight we went to sleep, however, strong reflectors and twenty policemen with automatic rifles pointed at us woke us up. When they threw us out of the house, we saw even more reflectors and policemen whose automatic rifles were ready to shoot. Fifteen of us were put in one police van, even though they had three, kept us for a half an hour and then drove us around until they stopped at an obscure house. They kept us there for another two hours, in some kind of jail cells, without interrogating us. Then they released us, and we had to walk three hours to Ljubljana, where, at the first traffic light, another police van waited for us, and this then lasted for another hour…”

Eventually, none of those sentenced went to prison. Đinđić explained his acquittal in the interview: “We filed an appeal; however, we received amnesty entirely irregularly. We were expecting to serve the sentence; instead of it, we got a document saying that our sentence was changed to probation. Therefore, they did not pardon us based on our appeal. Rather they found us guilty, and this verdict went into our personal records, which made it impossible for me to find even a bookseller position afterwards. Since I knew a few professors from the Korčula Summer School, among them Habermas, he suggested me to come and to do my PhD under his supervision in Germany. At that time, an aura around the whole anti-communist movement still existed and there was a lot more will to help than today.”

The interview can be found in the personal collection in box number 3.