Pál Schiffer (1911–2001) was one of the most significant documentary filmmakers in Hungary in the 20th century. He was the child of a family that played a leading role in the history of the Hungarian social democratic movement. After the Second World War, his grandfather, Árpád Szakasits, was one of the leaders of the Hungarian Social Democratic Party who urged close cooperation with the communists. Szakasits became the president of the united party in 1948. He was also elected president of Hungary, but his career declined very rapidly. In 1950, he was imprisoned, as was Schiffer’s father, Pál Schiffer sr. This is significant because the consequence was a radical change in the status of their family. As Pál Schiffer remembered in 1988, as a little boy “usually I was taken to the Gorky School in a Mercedes from our seven bedroom villa on Rózsadomb, where I had a fantastically furnished room.” Until 1950, he was living in a bubble in other terms too: “everybody around me was talking about how wonderfully happy the country in which we lived was: everybody was content, feeling great, everybody was an enthusiastic supporter of the system.” When his father and grandfather were apprehended by the political police, they had to move from the capital to the city of Debrecen, where they lived in a small flat in a working-class neighbourhood. As a schoolboy, his entire world turned upside down, and he was totally shocked. He was confronted with the fact that people in his new environment were malcontent: “they were criticizing the system, complaining that they had to stand in line for bread, meat, and sugar, that they were afraid of the ÁVH [State Protection Authority], the police, the party secretary, and one another. I had to face it, I had been living a lie.” The six years that he spent in Debrecen were a formative experience for him, and when his family was rehabilitated and was able to moved back to Budapest in 1956, he decided to share his experiences with the members of the Budapest elite who were living relatively well. His father and grandfather became leading cadres of the Kádár regime, but he did not forget the Roma he had seen in Debrecen and the surrounding rural areas in eastern Hungary.

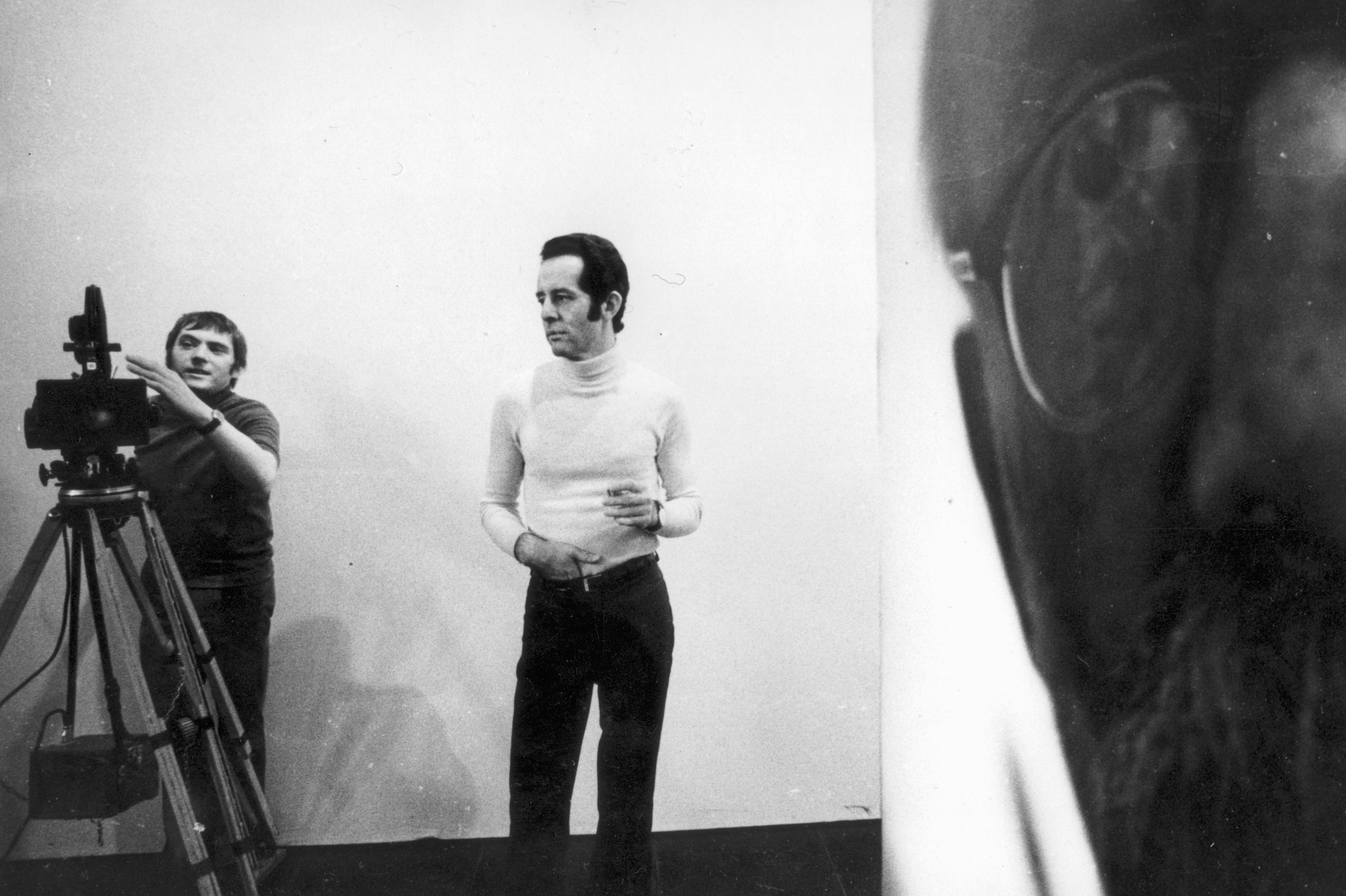

Pál Schiffer jr. graduated from the Academy of Drama and Film in 1963 and started to work at the Department of News and Documentary Films at the Mafilm Hungarian Film Studios. He also became a member of the Béla Balázs Studio, which gave young filmmakers opportunities to experiment. This is where he shot his first well-known documentary, Fekete vonat (Black train, 1970) on Roma communities trying to cope with the hardships of life, especially unemployment. As cultural sociologist Ferenc Hammer and film historian Andrea Pócsik observe, the film is overrated and does not reflect the insights of cutting-edge sociology of the time exemplified by the research of István Kemény. Schiffer himself did not consider this film a masterpiece either, and he was critical of his practices in the 1960s. As he explained in 1988, in the first phase of his career, he wanted to create documentaries for the cadres to make them aware of the dysfunctionalities of the system and urge them to consider reform. In 1972, by which time it had become clear that no real attempts at reform would be made by the regime, however, he realized that this top down approach would not work. This affected Schiffer’s filmmaking practice, and it also prompted him to invest more in arranging public screenings and to try to make a difference in wider local communities.

Schiffer started to accompany Kemény on his field research trips in the late 1960s, but only his later documentaries made in the 1970s show the influence of some of the findings of Kemény’s work. These findings were summarized in his fictional documentary Gyuri Cséplő (1978), which suggested that the question of poverty is not an ethnic issue and confronted viewers with social injustice and images of extreme poverty. However, according to Pócsik, their significance notwithstanding, these films ignored or failed to convey findings of Kemény’s research that transgressed the limits of officially acceptable discourse. They failed to raise the question of the responsibility of the system for keeping the poor in a miserable situation and failing to prize the grassroots efforts by the poor to make a change. Even so, the censors (the Chief Directorate of Film Industry) ordered some shorter parts of the film to be cut.

In the 1980s, Schiffer continued to make documentaries on people living in parts of the country other than Budapest in marginalized statuses. On the eve of the regime change, he reflected on acting ion his own: his work was not in line with official cultural politics, the urban audience was not interested in rural poverty, the populist-nationalists felt his approach was alien to them, and for the democratic opposition he was not politically outspoken enough. Schiffer summarized his approach: “I think history is what happens to those who are suffering under history, to those who are not asked about what they want, to those who do not have a choice. But what has been loosened and tightened by the upper circles of politics, these people have tried to accommodate to this and take advantage of it for the benefit of their community.” He tried to avoid passing judgment and identifying who was responsible for the state of affairs, and instead he offered descriptions of small local communities entirely detached from politics and often deprived of agency. This enabled him to raise issues that were awkward for the Kádár regime and also to respond in a distinctive way to the general apolitical atmosphere of Hungary in the 1980s, when the principal strategy for citizens was non-engagement.