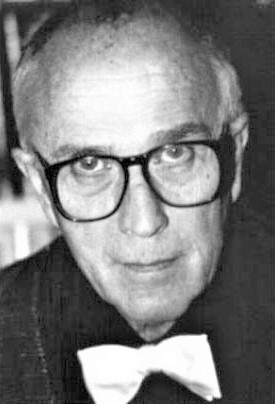

Ion Negoițescu (10 August 1921, Cluj – 6 February 1993, Munich) was a Romanian writer and literary critic, who began his career under the intellectual influence of the philosopher Lucian Blaga and the Sibiu Literary Circle, a leading literary group in WWII Romania. Negoițescu made an early literary debut in 1937, with the publication of a poem in the magazine Naţiunea română (The Romanian Nation) in his native town of Cluj. In 1941, he became a student at the Faculty of Letters and Philosophy in Cluj, which was moved to Sibiu when northern Transylvania, including Cluj, came under Hungarian rule in the aftermath of the Second Vienna Award. Negoițescu was first attracted by the Romanian extreme right movement, the Iron Guard, and even became a member of this political party (Bouleanu 2016). However, under the influence of the modernist Sibiu Literary Circle, he changed his political convictions later. Thus, in 1943 he signed together with other writers The Manifesto of the Sibiu Literary Circle, in which they protested against the intrusion of the political regime, i.e., the Ion Antonescu military dictatorship, in the literary field. In reaction, the signatories of the manifesto could no longer publish in literary magazines (Negoițescu 1990, 6–12, 41). In January 1945, these writers established Revista Cercului Literar (The magazine of the literary circle), but only a few issues could be published because the communist-dominated government closed it six months later (Negoițescu 1990, 6–12, 41–42).

In 1947, Negoițescu received the Young Writers’ Prize of the Royal Foundations for the volume in manuscript Romanian poets. His refusal to collaborate with the new communist regime led to his marginalisation. He could not publish until 1956 and had to work as a librarian in order to support himself (Bouleanu 2016). The limited liberalisation that followed Nikita Khrushchev’s de-Stalinisation campaign allowed Negoițescu to re-enter literary life, and he published several articles about the Romanian writers censored at the beginning of the 1950s. After the reversal of the political liberalisation and the tightening of censorship Negoițescu was accused of “subverting the foundations of socialist literature,” put on the list of censored authors and expelled from the Writers’ Union in Romania. At the same time, Negoițescu was interrogated by the Romanian secret police, the Securitate, whose officers did not hesitate to use violence, threats and insults against him. He was finally imprisoned on political grounds in 1961, and stayed in the Jilava prison until 1964.

As the communist regime declared a general amnesty for all political prison in 1964, he was released from prison and started to work as an editor at two Romanian literary magazines Luceafărul and Viața Românească. Apart from the collaboration with these literary reviews, Negoițescu published a volume of literary criticism and one of poems composed while in prison. In 1968 he published in the literary magazine Familia a draft of a History of Romanian Literature that sparked many controversies (Bouleanu 2016, Negoițescu 1990, 43–44). In 1974, on the National Day of Romania (23 August), Negoițescu tried to kill himself with an overdose of pills. Behind his dramatic gesture stood his desperation that his latest volume Lampa lui Aladin (Aladin’s Lamp) had been removed from libraries and destroyed. Another reason for his radical gesture was his sexual orientation. Negoițescu had openly assumed a gay identity, in spite of the fact that homosexuality was incriminated by law under communism and thus he had to live under the constant threat of being arrested (Bouleanu 2016; C. Petrescu 2013, 131).

The most problematic period in Negoițescu’s life began on 3 March 1977, when he personally addressed a letter of solidarity to his fellow writer, Paul Goma. Negoițescu’s letter actually reviewed the evolution of Romanian literature since the communist takeover and argued that Ceauşescu’s nationalistic turn endangered Romanian literature by favouring the promotion of mediocrity instead of real talents and by isolating Romanian culture from the rest of the world (C. Petrescu 2013, 130–131). The letter also contained a “subjective” perspective as Negoițescu also described the persecutions he had been subjected to by the communist authorities (Negoițescu 1990, 31). Copies of this letter reached Radio Free Europe with the help of Paul Goma and the president of the Writers’ Union of Romania. Negoițescu also tried to encourage his fellow writers and friends, including Ion Vianu, to join the emerging Goma movement. Because he refused the peace offers made by the regime, which included the promise of being able to publish his books and to travel abroad, he was arrested by the Securitate and interrogated for forty-eight hours. However, he was released due to pressure from influential writers (Negoițescu 1990, 31–37). As he faced the prospect of a harsh penal sentence for homosexuality, Negoițescu had to disavow his endorsement of the Goma movement by an article entitled

Despre patriotism (About patriotism), which he published in the leading literary magazine

România Literară (Literary Romania). The article practically signified the end of Negoițescu’s dissidence, as he praised the regime and mentioned that he opposed the use of his person and writings against his country (C. Petrescu 2013, 137). Taking advantage of an academic trip abroad, Ion Negoițescu left Romania for good and settled in Munich, Germany, in 1983. He continued his activity as a writer and defender of freedom of speech and human rights, becoming an important voice of the Romanian exile community and a very active collaborator of Radio Free Europe, Deutsche Welle and the BBC (Bouleanu 2016).